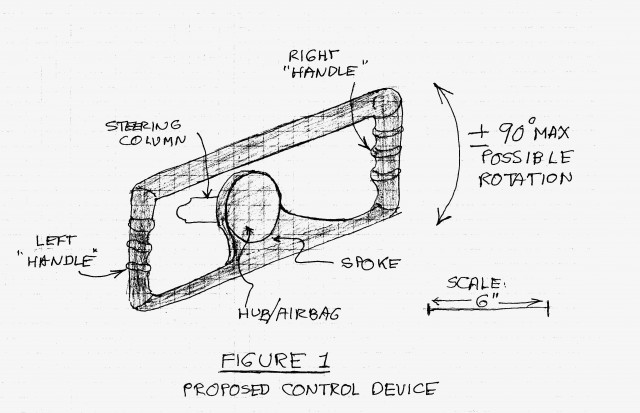

Perhaps it’s time to reinvent the wheel. Seeking improved safety, a Florida engineer wants to nix the standard round steering wheel and replace it with a rectangular device that turns only 90 degrees in either direction. The design takes a “hands firmly planted” approach, eliminating the need for the hand-over-hand maneuver typically used to make sharp turns. This could help drivers maintain constant control of a vehicle even at high speeds, which could mean fewer crashes.

At the annual meeting of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society held last month, Rene Guerster, an engineer at the University of Central Florida, presented his idea as a formal proposal.

“I learned to drive a farm truck when I was nine,” Guerster explains. “That’s where my fascination with steering began.” The problem with steering, he believes, is that it isn’t intuitive. So everyone has their own way of doing it.

Looking for a better approach, Guerster included up-to-date safety technology, including steer-by-wireand anti-lock-braking, into his design. Steer-by-wire uses a computer in the car to help the steering wheel control the front tires. The computer reads the driver’s turning motion and, based on the vehicle’s speed, calculates a safe turning angle for the front wheels. Meanwhile, the anti-lock-braking technology lets a driver maneuver to avoid objects even while coming to a screeching halt. Guerster hopes to maximize the effectiveness of these technologies by hitching them to his own device.

Guerster has mockups of his design but he has never actually used it to drive—at least, not yet. He hopes to begin tests within the next year, and is planning to conduct a study in which participants of different ages, genders and levels of driving experience could try the device. Participants would be tested in three scenarios: driving along a straight road at a constant speed of 60 miles per hour, a winding road at 45 miles per hour, and making a sudden lane change at 30 miles per hour.

To integrate the steer-by-wire system effectively, Guerster will have to make sure the steering device is in perfect sync with the front wheels so that a big turn of the wheel will mean a big turn of the tires, and vice versa. To make sure the steering device is responsive without being too sensitive, he plans to test three algorithms—calculations programmed to tell the car’s computer what to do—that correspond to different levels of turning sensitivity.

Steering wheels have gone through the motions for more than a century. Originally called helms, they were used to steer boats before they first appeared in French automobiles. From there, they were incorporated into American cars by Henry Ford starting in 1908 and have been the standard ever since.

Any attempt to radically alter a design that has been so deeply entrenched for so long faces huge obstacles – including making sure that untrained drivers can use it without fear.

“The device can be made from the same materials as a regular [steering] wheel”, says Guerster, who has already applied for a patent. “The real cost is in developing the microprocessor and doing the testing to satisfy” federal regulators.

Engineers uninvolved in the project say Guerster has a long road ahead of him, but that his idea is worth exploring. Daniel Hannon, a human factors engineer at Tufts University in Massachusetts, worries that the three-and-nine o’clock hand position Geurster advocates may get uncomfortable on longer trips, leading to safety issues. “I would want the researcher to include some kind of analysis on the comfort of the driver while using the device,” Hannon says.

Richard Ferraro, a cognitive scientist at the University of North Dakota, was present at the conference on 4 October in San Diego where Guerster presented. He suggests introducing the tool gradually and giving drivers an option. “For a truck driver on a long stretch of road, I could see a tool like this being very useful. But if you are headed out for a bottle of milk, maybe you don’t need it as much,” he said.

Ferraro adds that today’s drivers are accustomed to changing technology. As a kid, he recalls televisions having three channels, getting up to change the dial and being perfectly happy with that. “Then there was the introduction of satellite TV, remote controls, and suddenly you didn’t need to get up,” says Ferraro. “People had trouble at first, but they adapted and now it’s common. I think the same would be true for this new device.”

Published in Scienceline